"JUST A SMALL TOWN GIRL, livin' in a lonely world. She took the midnight train goin' anywhere."

|

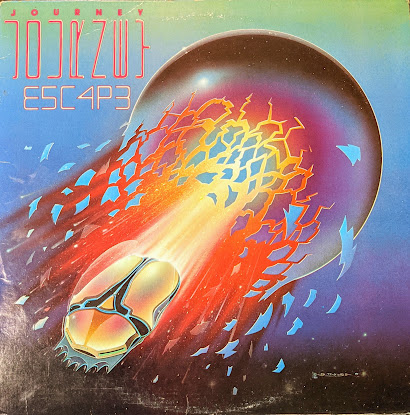

| The L.P. |

"Just a city boy, born and raised in South Detroit! He took the midnight train goin' anywhere!"

Now stop and locate South Detroit on a map of Michigan. Then again, don't bother. It's not there. The only thing directly south of motor city is Windsor, Ontario, and that's not even in the same country, let alone the same city or state

The real lesson here is to never let geographical inaccuracy get in the way of a stellar pop song. Steve Perry and Journey sure as heck didn't and, as a result, Don't Stop Believin' is still with us like some post-boomer national anthem four decades after its release.

Everyone knows the words, from the kids from Glee to Tony Soprano. The song became a staple at hockey games in Detroit and baseball games in San Francisco. It's even been deconstructed by musicologist Rick Beato.

|

| 45-degree turn |

Its cultural contemporaries included the movies Raiders of the Lost Ark, Superman II, Chariots of Fire and For Your Eyes Only. The latter two films spun off their own charting singles, a Vangelis instrumental from the former and a Sheena Easton-sung title song from the latter. Nominated for an Academy Award for best original song, it lost out to The Best that You Can Do, from the comedy Arthur.

All of this during what was kind of a bleak year.

President Ronald Reagan survived an assassination attempt, so too did Pope John Paul II. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat did not. Irish Republican Army member Bobby Sands staged a fatal hunger strike. Major League Baseball shut down from June 12 to August 9 because of a labor dispute, wiping out more than a third of its scheduled games.

Escape was recorded that spring and released at the end of July.

|

| Side 1, Track 1 |

It entered the Billboard Hot 100 at number 56, the week of Oct. 31, just behind Trouble by Lindsay Buckingham. Also on the charts then: Harden My Heart by Quarterflash, Olivia Newton John's Physical, the theme from Hill Street Blues and that number one song from Arthur.

Still on the chart, an earlier Journey single, Who's Crying Now which went to number 4. Still to come, their power ballad, Open Arms, which topped out at number two behind the J. Geils Band's Centerfold.

Don't Stop Believin' climbed only to number 9, lingering on the charts for 16 weeks, but it never really faded away. Journey's signature song became instead a part of the firmament, a touchstone embedded in our pop-cultural consciousness.

"Hold on to the feeling..," Steve Perry sang in the outro, and hold on we have. It's the most digitally downloaded song of the 20th Century.

______________________________

For Joan and Ian, who -- in these uncertain times -- now have the ultimate reason to believe.

-- Follow me on Twitter @paperboyarchive